NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2019 Apr 21, 13:05 -0700

That phrase I mentioned, Nuit Américaine, is an expression from French film-making which is equivalent to a "day for night" in American film-making. When a scene is filmed in daylight under-exposed and/or using filters and films that create the illusion of night, that's a "day for night". The terrestrial portion of this attractive image appears to be an example of a "day for night". Notice the shadows of the trees and the bridge and even the lighting on the cathedral. There are prominent shadows pointing northeast. Moonlight maybe? No, not moonlight --at least not on the date consistent with the astronomical portion of the image. From the position of the comet, we can determine the date. According to Bond's detailed account of the comet, the comet was very close to Arcturus on October 5, 1858. The image apparently represents the appearance on October 3 or 4. The Moon was a thin morning crescent at that time and not in the sky in the evening. Bond comments on the fact that the comet was so spectacular because there was no interfering moonlight.

In this image of Comet Donati over Notre Dame, we clearly have some sort of artwork. The sky and comet are surely a drawing of some sort. Joe Rao (replying on FB) even proposed an example from Harvard that was made in 1858 that might very well have been the original, as shown below. Notice the orientation of the stars in Bootes. At the altitude as shown, the constellation would be more vertical in the latitude of Paris, which is well north of Massachusetts. It seems likely that this composite was constructed at a much later date (I've seen a publication date of 1877 but can't find that anymore).

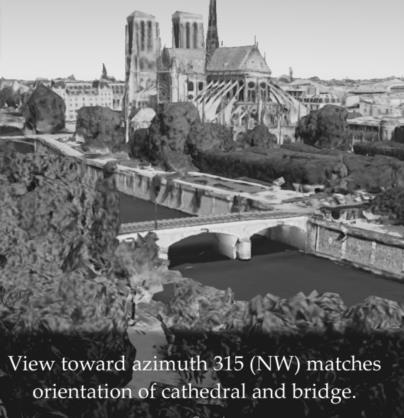

Using the terrestrial portion of the image, we can reasonably well determine the photographer's location. The alignment of the piers of the bridge over the Seine with elements of the cathedral narrows things down quite well. The photographer was apparently on a rooftop of a high floor southeast of the cathedral (where the white lines cross in the image below). This also tightly constrains the viewing azimuth and would place Arcturus on an azimuth close to 315°. Unfortunately, Arcturus never gets that far north as seen from Paris. At the approximate altitude displayed in the image, Arcturus would be at most a few degrees north of west. So the alignment is out by 40° or even more. The angular scale isn't too bad though, off by perhaps 30% from ground to sky.

So my best theory is that the creator of the image had seen a spectacular view of this "great comet" above the cathedral many years earlier and managed to unite an old drawing of the view with a more recent photo of the cathedral and surroundings taken from a different location. So it's not right in detail, but something very much like this view would have been seen in central Paris in 1858.

As for photographing the comet itself, 1858 was still very early in the history of photography, and yet this was, as it turns out, the first comet successfully photographed, again by George Bond. The photo was a mere smudge on a glass plate. Details here.

Astronomical photography has always been a form of illusion from the beginning. Long expsoure images do not represent the actual appearances of astronomical objects. The Orion Nebula or the Andromeda Galaxy which look so magnificent in long-exposure photos are faint clouds when seen through the largest of telescopes (or even from "close up" if you could travel to them). It's difficult to capture the visual "impression" of a faint astronomical object, like the tail of a great comet, but in truth this artistic composite does a decent job.

Frank Reed