NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2017 Jul 24, 10:57 -0700

David Pike, you wrote:

"Can you ever solve the case digitally when you have no idea where you are, and you can’t even identify the three bright objects visually? In other words, can you design and incorporate a device to identify the three unknown bright objects from their electromagnetic transmissions or their position in relation to background clutter in the field of view."

If you have measured three altitudes, then the solution is relatively easy by geometry, given some reasonable limit on brightness (no stars fainter than mag 2.0, e.g.). Let's set aside the easy case. Suppose we have a single star instead and no DR. This is a purely theoretical case, but there are still options here. At the low tech end, you make your observation in twilight... alas, only one star. And then you wait. When the fainter stars come out, you can identify your unknown in the usual way by looking at nearby faint stars --looking at the "bakground clutter" just as you said. The Air Almanac included finder charts with nearby faint stars, didn't it? The principle is the same. Even automated star trackers use this approach: pattern-matching in a narrow field of view using a database.

But do stars have "fingerprints"? Sure. Although there are spectral categories, not two stars in a thousand actually have indistinguishable spectra. And we don't need a full spectrum to take advantage of this. A common surrogate in astronomy is the "B-V" magnitude. So to get good "fingerprints" of sufficient sensitivity to distinguish the brightest thousand stars, we would need to measure the brightness of each in the visual or "V" sense and then also in the blue or "B" porition of the spectrum. After some calibration that pair of numbers would allow us to identify with good confidence each and every one of those stars.

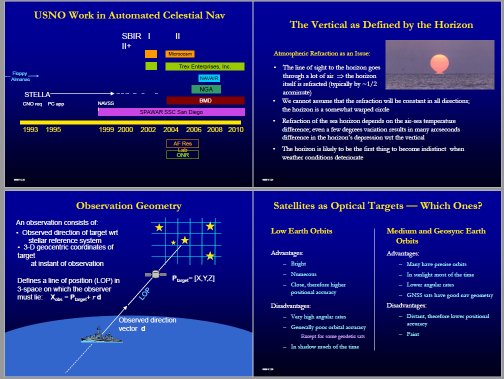

By the way, those modern star trackers are described in George Kaplan's slides (linked again below). These trackers are "off the shelf" complete solutions for orientation that work by simple pattern matching. The database of stars is included on the chips. All you have to do is expose it to a sky full of stars and in a few moments it will directly output the exact direction on the celestial sphere it's looking at. These devices became standard in spacecraft in the 1970s, replacing the last bit of human guidance from the Apollo era. This is now a "mature technology".

You concluded:

"A device which did all of those things would be worth having, especially if it could also work through cloud. "

Heh. Yeah. X-ray vision would be nice. Or... just stick it on a drone and fly above the clouds! Perhaps not every small boater could afford a drone capable of flying reliably to 15 km altitude, but that does solve the weather problem. And in addition, you can see the stars in daylight from that altitude. This is also highlighted in Kaplan's presentation.

Frank Reed

George Kaplan's presentation: