NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Gary LaPook

Date: 2011 Feb 12, 00:55 -0800

(I am also attaching this as a PDF file.)

I have examined Amelia Earhart’s navigation from Natal to Dakar near the beginning of her

flight around the world. Although this leg took place well before the flight from Lae to Howland,

it has been seen as relevant in unraveling the final mystery as it may shine light on the

interaction between Earhart and Noonan. But just like the rest of this story, the information

concerning the flight across the Atlantic is confusing, contradictory, incomplete and difficult to

interpret.

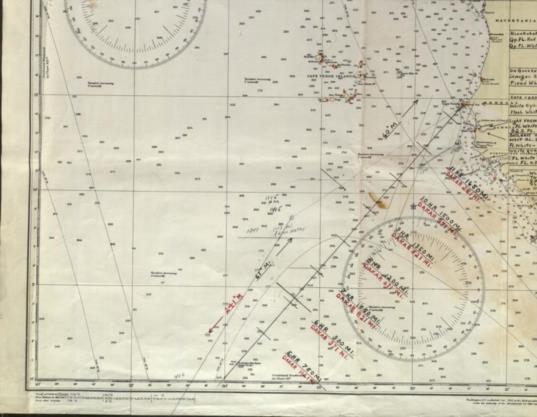

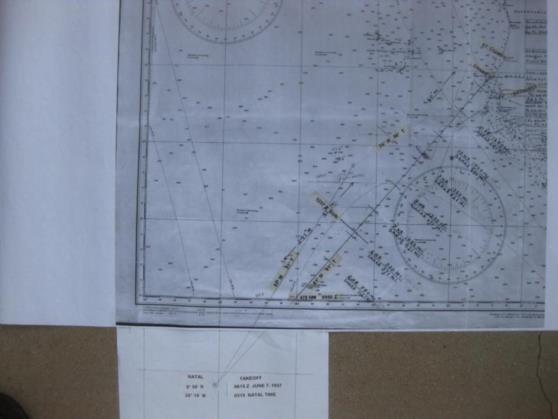

I obtained a copy of Noonan’s actual chart that he used on the flight from Natal to Dakar. The

original is kept in the archives of Purdue University and I had the archivist scan it for me.

(TIGHAR sells a copy of what it claims is this chart but it IS NOT an accurate copy of the actual

chart, markings have been erased and, even more inexplicably, it has added markings and

notations, so its provenance is suspect.)

Earhart and Noonan departed Natal, Brazil at 0615 Z (Greenwich Mean Time) on June 7, 1937

for Dakar and landed thirteen hours and twelve minutes later at 1927 Z in Africa but at Saint

Louis, about 116 SM north of their planned destination of Dakar. ( Earhart said it was 163 SM.)

Amelia explained it this way:

“When we first sighted the African coast, thick haze prevailed and for some time no position

sight had been possible. My navigator indicated that we should turn south. Had we done so, a

half hour would have brought us to Dakar. But a "left turn" seemed to me in order and after

fifty miles of flying along the coast, we found ourselves at St. Louis, Senegal.” (Last Flight, page

119)

A careful examination of the actual chart work that Noonan did on this flight might further

explain what actually happened. (I have also examined Noonan’s chart for the flight from

California to Hawaii so I am familiar with his methodology.)

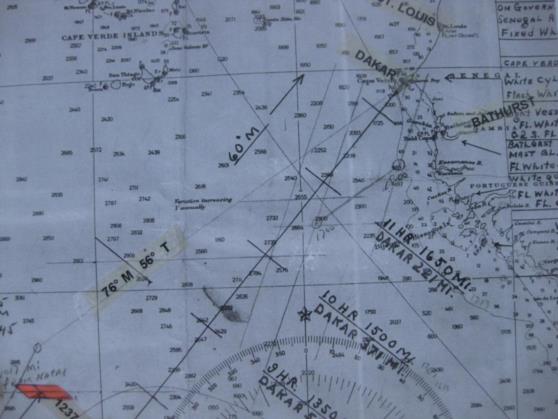

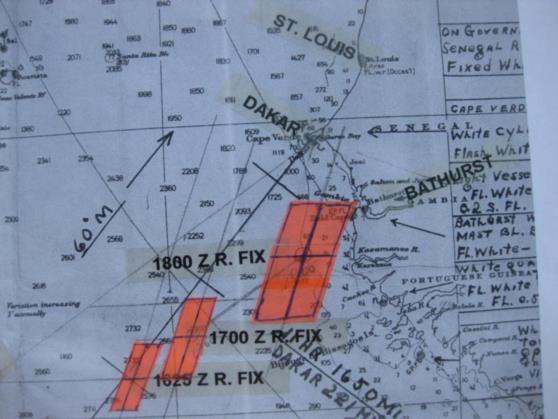

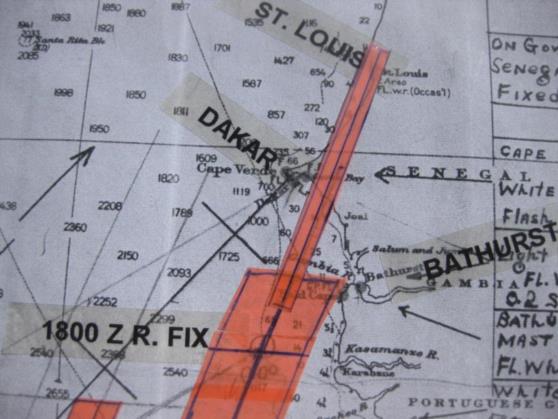

I have attached a copy of the southwestern portion of “North Atlantic Ocean, Southeastern Sheet,

(1930)”, the marine chart used by Noonan. I have also attached a black and white large scale

printout of this chart on which I have made annotations. (See maps 1 and 2 and image 3.) This

chart starts at the equator. The first thing you notice on the chart is the preplanned course line

marked at hourly intervals, every 150 statute miles (SM) since the planned ground speed was

150 mph. The last mark is at the 1800 SM point at 12 hours. From this last mark to Dakar is 71

SM for a total of 1871 SM, making the estimated flight time twelve hours and 28 minutes and

the estimated time of arrival (ETA) 1843 Z. (Earhart’s clock was set to Natal time which is three

hours slow on GMT and her notes are in Natal time. I have converted them to GMT as this is the

time used by Noonan for his notations on the chart. I also use nautical miles (NM) as these are

the miles used by Noonan and all navigators. A nautical mile is 15% longer than a statute mile so

the distance from Natal to Dakar is 1627 NM. Since navigators use nautical miles for distances

they also use knots for speeds, one knot being one nautical mile per hour. The planned ground

speed was 150 mph which is the same as 130.4 K (knots).)

The true course runs 41̊. Parallel to the course line you find the notation “241̊ M — 61̊M” and

further along “60̊ M.” This shows the magnetic course for use with reference to the magnetic

compass and is the true course adjusted for the magnetic variation of 20̊ west for the first part of

the flight and 19̊ west for the final portion.

Further to the west is another line running 31̊ T (true), 051̊ M. On my annotated chart I have

attached an extension at the bottom so that I could plot the departure airport at Natal at 5̊ 54'

south, 35̊ 15' west. Noonan did the same thing as we can see the two lines already mentioned

run across the neat line onto the border and converge on Natal. You can see Noonan’s notation

next to the leftmost line of “410" which is the distance in NM from Natal to the equator along

this line. I added a similar notation for the course line which crosses the equator 470 NM from

Natal.

Earhart wrote that they crossed the equator at 0950 Z (6:50 a.m.) in her notebook. This was

based on dead reckoning (moving the position based on the course flown and the distance

covered) and we can determine that they were following the course line and not the leftmost line

by this notebook entry. The flying time to this point was 3:35 which at 130.4 K means they had

traveled 467 NM which is consistent with the distance along the course line to the equator. Had

they been following the leftmost line they would have crossed the equator 26 minutes earlier at

0924 Z.

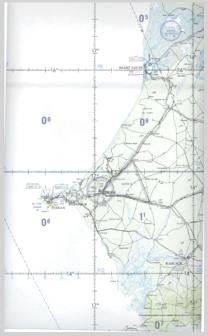

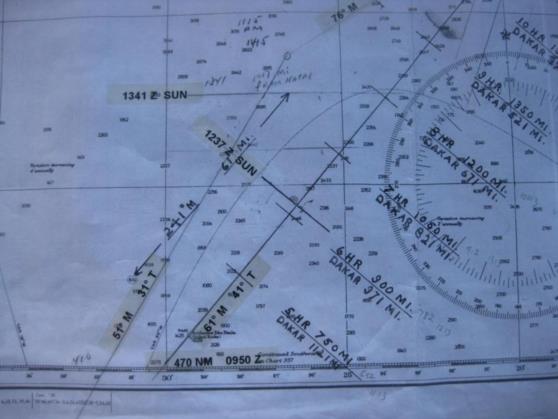

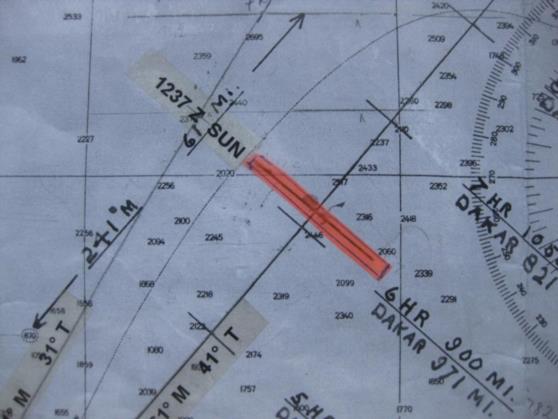

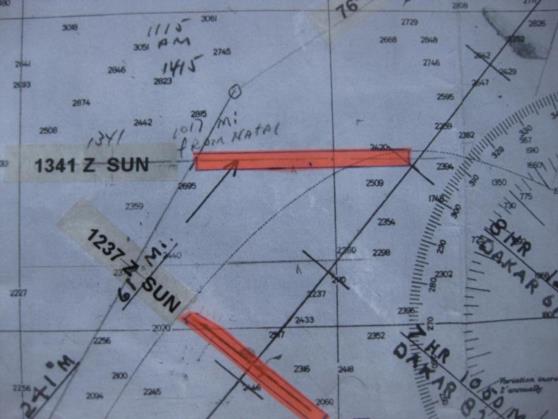

At 1237 Z Noonan measured the sun’s altitude with his Bendix bubble octant (a kind of a

sextant) through the cockpit windshield as the sun was almost directly in front of them and he

would have measured the altitude as 65̊ 34'. After doing the appropriate computations, Noonan

drew a line of position (LOP) across the course line running 130̊ T - 310̊ T which was at right

angles to the azimuth of the sun which was 040̊ T. (See image 4.) Although Noonan didn’t write

the time of this sight down on the chart, we know it was 1237 Z as it was at that time that the

azimuth of the sun was 040̊ T at that point on the course line. Any earlier and the azimuth

would have been more,, any later and the azimuth would have been less. (Contrary to what is

observed in the U. S., from their location the sun moved counter-clockwise across the sky.) The

LOP represented their most probable location, they should be somewhere along this line. This

LOP is 809 NM from Natal and the elapsed time was 6:22 so the ground speed had been 127 K

(146 mph.)

Since there is some uncertainty in celestial observations, the LOP is actually a band 14 NM

thick extending 7 NM on each side of the LOP. It is very unlikely that a sextant reading will

produce an LOP that is more than 7 NM in error so this band should contain virtually all possible

locations of the plane and the plane is actually most likely to be nearer the center than the edges.

However, this one LOP couldn’t give Noonan his exact location as they could have been

anywhere along it but he could put some bounds on this uncertainty. (This is no more

mysterious than your saying that you are somewhere on Second Avenue.) A generally accepted

rule used by flight navigators is that the uncertainty of a dead reckoned position increases as

10% of the distance covered since the last fix. They had flown 809 NM from Natal so the

uncertainty extends 80.9 NM along the LOP in each direction from the course line making the

LOP 162 NM long and 14 NM thick. I have indicated the extent of the uncertainty band on the

hi-liter tape. (See image 5.)

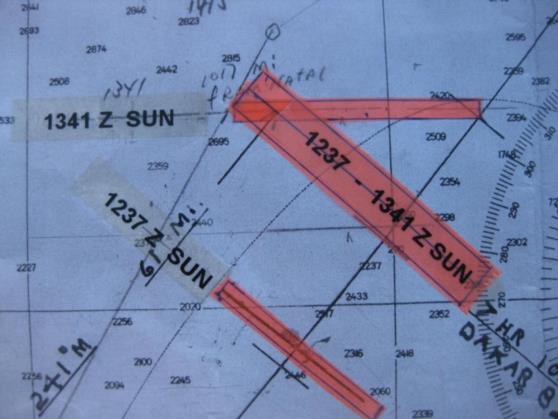

At 1341 Z Noonan took another observation of the sun, this time from the left side cabin

window. He would have measured 74̊ 48' with his octant. After computation, he drew an LOP

running 90̊ T - 270̊ T meaning the azimuth to the sun was straight north, within a couple of

minutes of noon. At this point Noonan had reason to believe that he was west of the course line

at a longitude of 25̊ 35' west. We know this because at 1341 Z the Greenwich Hour Angle

(GHA) of the sun, the same as its longitude, was 25̊ 35', Noonan would have found this in his

Nautical Almanac. Only if the airplane’s position was at the same longitude as the sun would the

sun’s azimuth be straight north. If they were still on the course line then noon would have

occurred earlier at 1335 Z at a longitude 24̊ 05', about 90 NM further east. Noonan most likely

had determined that they were to the left of course by measuring the plane’s drift with his Mk 2

driftmeter. Similarly to the first LOP, this LOP was also 14 NM thick but was 200 NM long as

they were now about 1000 NM from the last fix, the departure airport of Natal. Noonan drew this

LOP and labeled it “1341" and extended it so that it crossed the course line and also the leftmost

line running at 31̊ T. (See image 6.) Since this LOP runs straight east and west it defines a

latitude of 7̊ 37' north. This LOP crosses the course line 1070 NM from Natal and also crosses

the leftmost line only 943 NM from Natal. We can make an estimate of where along the LOP the

plane was. The plane had been flying for 7:26 so if they were on the leftmost line then their

average ground speed had been 127 K (146 mph.) If they were following the course line then

their ground speed would have been 144 K (165 mph) which is also reasonable with only a 14 K

tailwind, which would not be unusual. Earhart wrote in her notebook that they were flying at

6,000 feet, the temperature was 60 ̊ F, and the indicated airspeed was 140 mph thus making

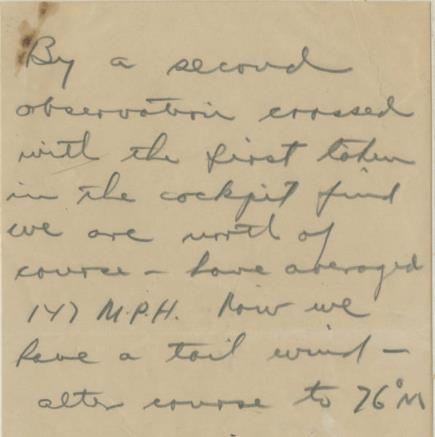

their true airspeed 155 mph, 5 mph faster than their planned speed. Noonan sent Earhart a note

saying that they had averaged 147 mph but also saying that they now had a tailwind so that

doesn’t help much. (I have attached a copy of this note which is kept at Purdue, see note 1.)

The note also said that by crossing the 1341 Z observation with the first observation that he had

determined that they were north of course, to the left of course. Noonan was talking about a

standard navigational method of advancing the earlier LOP to the time of the second LOP and

taking the point that they cross as a “running fix.” A normal “fix” is at the intersection of two

LOPs taken at the same time which is no different than stating that you are at the intersection of

Second Avenue and Main Street. A running fix is the same as your friend calling you on his cell

phone and saying “I have been driving east of Second Avenue and I passed Main street about a

mile back.” A running fix has more uncertainty than a normal fix since the navigator must

estimate the movement of the airplane between the two observations and advance the earlier

LOP as though it had been attached to the plane. Any error in this estimate will result in a similar

error in the running fix. This is where the skill of the navigator is critical and why navigation is

also an art and not entirely a science.

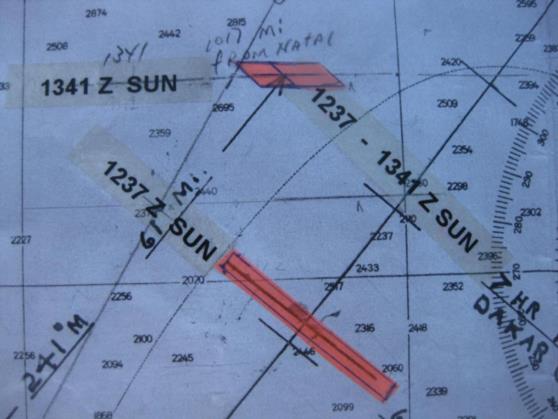

Even though Noonan said that crossing the two LOPs showed them to be to the left of course and

that they now had a tailwind, he did not actually do the chart work to do this but apparently just

used his experience to estimate where the running fix would have been. On my chart I have done

the chart work and have advanced the 1237 Z LOP along the course line (maintaining its

alignment) 139 NM, the distance that would have been covered by the plane at the flight planned

130 K speed for the 1:04 period between the two sights. The first LOP was originally 14 NM

thick but the uncertainty increases at a rate of 10% of the distance the LOP is moved adding an

additional 13.9 NM (call it 14 NM) to each side of the original band of uncertainty making the

band or uncertainty 42 NM thick after it is advanced. (The length also increases by the same

ratio but this is not important at this point.) The intersection of the 1341 Z LOP with the 1237 Z

advanced LOP marks the running fix and the overlap of their bands of uncertainty contains the

actual position of the aircraft. This area is 14 NM thick north to south (the uncertainty of the

1341 Z LOP) and extends 60 NM east and west (since the lines cross at an angle), constrained by

the overlap of the 1237 Z advanced LOP. (See image 7.) In image 8 I have removed the excess

length of the two LOPs leaving only the overlap which is the total area of uncertainty of the

running fix. (See images 8 and 9.) A navigator takes the actual intersection of the LOPs as the

running fix and does not draw in the uncertainty bands but he keeps them in mind and knows

that they grow bigger as time goes on.

The normal procedure is to mark the running fix on the chart and then lay off the new course

from that point to the destination but Noonan didn’t do this, why? He may have had some doubts

about the accuracy of the earlier sight and the rest of his chart work supports this theory. If we

look where the two LOPs intersect the course line we see that the distance between these two

intersections is 261 NM. For the plane to travel up the course line and cover the distance

between the two LOPs in 1:04 would require a ground speed of 245 K meaning a tailwind of 115

K which is impossible. So one of the LOPs is probably in error and Noonan apparently decided

that it was the 1237 Z LOP. Noonan advances the 1341 Z LOP three times to determine running

fixes and DR positions but never actually advances the 1237 Z LOP.

The next thing we see on the chart is a circle at the north end of the leftmost line labeled “1017

mi from Natal” and the time of “1115 AM, 1415” which gives the Natal time and the

Greenwich Mean Time. From this point a line was drawn to Dakar on a course of 76̊ M (56̊

T), the heading that Noonan’s note instructed Earhart to turn to. So what did this all mean? The

leftmost line runs 31̊ T, exactly ten degrees to the left of the course line. I think what Noonan

was doing here is that he knew that they were drifting to the left of the course line but he also

knew that he had not drifted more than the ten degrees delineated by this line. He then knew that

if he assumed the worst case, that he was ten degrees off course to the left, and then figured the

course from that point directly to Dakar and with the plane anywhere to the east or south of the

1415 Z point, turning to the new computed course, 76̊ M, would guarantee that they would

intercept the coastline south of Dakar. The further chart work shows that this worked as

intended.

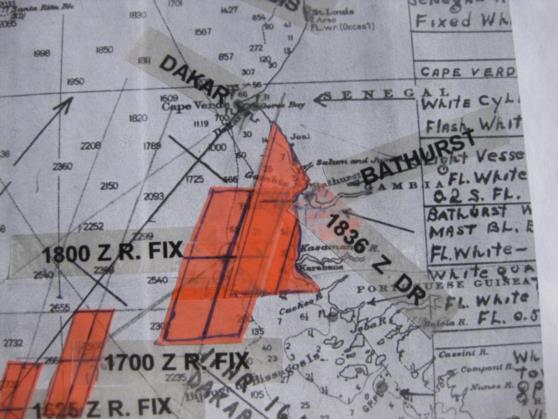

They flew on the course of 76̊ M and then at 1625 Z Noonan took another sun observation and

drew the resulting LOP on the chart. We know the time of this observation (it is not exact but

within five minutes) by the azimuth of the line and the distance on course that the plane traveled

between this line and the same line advanced to 1700 Z. If you extend the course line back from

the 1800 Z position though the 1700 Z position until in intersects the 1625 Z line you will

measure 78 NM and based on their ground speed this would take about 35 minutes placing this

earlier sun line and sun observation at about 1625 Z. He did not label this LOP. He then

advanced the 1341 Z LOP to intersect the new LOP and formed the 1625 Z running fix, which is

not labeled. (See image 10.) As before, the new LOP is 14 NM thick and runs 21̊ T since the

azimuth of the sun was 291̊ T. Since the 1341 Z LOP had been advanced for 2:44, a distance of

356 NM, the advanced 1341 Z LOP would have gotten about 71 NM thicker making it a total of

85 NM thick and this is in the north- south direction since this LOP itself ran east and west. I

have shown the resulting area of uncertainty on the chart. (See image 11.) These two LOPs were

then advanced twice to make the 1700 Z and the 1800 Z running fixes or DR positions. The 1625

Z LOP advanced to 1800 Z runs to St. Louis and nowhere near Dakar. (Elgin Long wrote that

Noonan actually took sun sights at 1700 Z and 1800 Z but the azimuths would have been

different if he had done so. Also, it was not Noonan’s practice to take sights on the hour as there

were no such sights taken on the much longer flight to Hawaii.) The areas of uncertainty

expanded each time these LOPs were advanced and I have illustrated these areas of uncertainty,

see illustrations 8,9 and 10. (This is not an important disagreement with Long. If Long is right

then the thickness of the uncertainty bands along the 1700 Z and 1800 Z LOPs were 14 NM

instead of getting wider as I have shown. My illustration shows the worst case. If Long is correct

then these positions are running fixes, if I am correct then they are actually DR positions) If you

draw a line through these last three positions on a bearing of 256̊ M (the reciprocal of 76̊ M )

you will see that it takes you back to the 1341 Z running fix. This shows that the plane was

within the uncertainty area of the 1341 Z running fix when the course was changed to 76̊ M.

The plane was not at the 1415 Z circled position, Noonan only used that point as a worst case

and used it to calculate the course to follow that would assure him that they would intercept the

coast south of Dakar. (See image 14.) If this isn’t clear, what Noonan was doing was a way to

deliberately aim off (like at Howland) to the south to assure that he didn’t pass to the north of

Dakar. Had he measured the course from the 1341 Z running fix to Dakar he would have found

68̊ M but by measuring from an arbitrary point 60 NM further north he found a course of 76̊

M, eight degrees further to the south, which would then cause the plane to end up well south of

Dakar.

Up to this point all we have seen is perfectly normal flight navigation as practiced by tens of

thousands of flight navigators during WW 2 and by additional thousands of B-52 navigators up

to the end of the Cold War, only twenty years ago. But from this point Noonan’s navigation

becomes strange. Looking at map1 you can see that there had been a line parallel to and between

the 1700 Z and 1800 Z LOPs that ran to Dakar but this line had been erased. We can also see that

the 1800 Z LOP runs to St. Louis, not to Dakar. The 1800 Z running fix (or DR) is 110 NM

south of the coast and even the extreme northern limit of the band of uncertainty is still 47 NM

south of the coast so there is no possibility that the plane could have hit the coast north of Dakar.

From this position it is 215 NM to St. Louis and from the northern edge of the band of

uncertainty it is 152 NM to St. Louis. If they turned towards St. Louis at 1800 Z to travel along

the LOP on a true course of 21̊, which is a magnetic course of 40̊, they would have crossed the

coastline 37 NM to the east of Dakar and even if they were at the extreme western edge of the

band of uncertainty, which is unlikely, they would still have hit the coast 10 NM east of Dakar.

(If Elgin Long is correct, that Noonan took an observation of the sun at 1800 Z, then the width of

the band of uncertainty would be greatly reduced, so even from its western edge, they would

have hit the coast 30 NM east of Dakar.) (See image 15.) The course to Dakar from the 1800 Z

position is 21̊ M (002̊ T) and the distance is 120 NM. Even from the nearest edge of the band

of uncertainty it is still 65 NM to Dakar. Flying along the 1800 Z line, when they hit the coast

they could easily have followed it to Dakar if they had wanted to go to Dakar rather than St.

Louis.

We can also look at the final stage of the flight by starting at the other end, at the landing, this is

a hard data point. The plane touched down in St. Louis at 1927 Z, 1:27 after the 1800 Z running

fix (or DR). Cruising at 130 K for 1:27 means the plane would have covered only 188 NM so we

know the plane had to be within a circle of that radius, centered on St. Louis, by 1800 Z. From

the 1800 Z running fix (or DR) it was 215 NM to St. Louis but only 152 NM from the northern

edge of the uncertainty band so the plane would have been somewhere in the northern portion at

1800 Z.

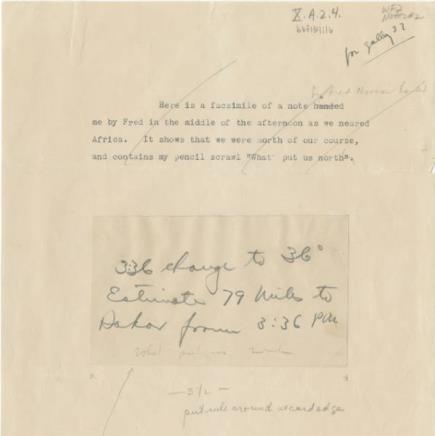

Now it gets even stranger. Earhart produced a note from Noonan that she received in flight

telling her to turn to 36̊ M at 1836 Z (3:36 p.m. Natal time). (See note 2.) This magnetic

heading would have caused the plane to fly north- northeast, parallel to the 1800 Z line, which

ran 40̊ M, with an allowance of a 4̊ wind correction angle for a light wind out of the west. But,

since this turn would not have occurred until 36 minutes later, the plane would have traveled 78

NM further to the northeast prior to making the turn. There is no notation on the chart indicating

this 1836 Z DR position. I plotted it on my chart and it falls almost directly over the town of

Bathurst (now called Banjul.) The band of uncertainty at the 1836 Z DR position is a bit larger

than the 1800 Z band and they overlap. (See image 16.) But we can eliminate from this band of

uncertainty that portion that is over land since they would have seen the coastline below them.

(See image 17.) A turn from the 1836 Z position to a heading of 36̊ M would have taken them

into “deepest, darkest, Africa” and nowhere near either Dakar or St. Louis. (See image 18.) From

the 1836 Z position above Bathurst to St. Louis is 160 NM but the time remaining to landing

would have been only 51 minutes so the plane would have had to fly at 188 K to make it, so we

know the plane was not at that position at that time. At its 130 K cruising speed the plane could

only cover 110 NM in 51 minutes. From the nearest edge of the band of uncertainty it was only

80 NM so the plane could have been in the northern section at 1836 Z. But Dakar was only 95

NM from the 1836 Z position so it would have been quicker and easier for them to just follow

the coastline there and it was even closer with the plane in the northern sector.

Just flying on a heading of 36̊ M was not likely to take them directly to St. Louis and might

have gotten them lost in the jungle. To avoid this possibility, and to ensure that they found St.

Louis, all they had to do was turn to a heading of about 345̊ T (004̊ M) as soon as they saw the

coast. This heading would have worked no matter where exactly they hit the coast, after turning

at 1800 Z or at 1836 Z. This heading would have taken them across the Cape Verde peninsula to

intercept the coastline between Dakar and St. Louis and would have guaranteed that they did not

overshoot St. Louis. Earhart said that they hit the coastline between Dakar and St. Louis and I

believe her, only they hit it coming from the land side, not coming in from over the ocean. Then,

like she said, they followed the shoreline to St. Louis, as planned.

Of course the reason the Dakar story had relevance to the final disappearance is that it offered an

explanation for why they were unable to find Howland. It seemed possible, at the end, that

Earhart refused, as she had done on the approach to Dakar, to follow Noonan's advice on the

heading to follow that would have taken them the Howland.

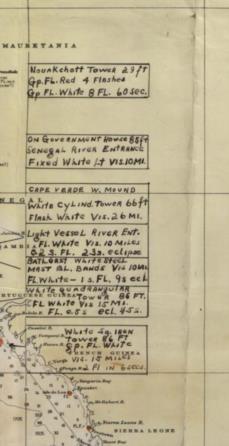

I have attached a portion of aeronautical chart ONC K-0 depicting Dakar and St. Louis which I

think will be of interest. (See chart 3.)

When I first heard the "I turned the wrong way when hitting the coast of Africa" story, I assumed

that the coast, at that point, ran in a straight line so that AE could reasonably question which side

of Dakar they were actually on. Now however, looking at this chart, it is impossible to believe

that story. The coast north of Dakar trends 040º T while south it trends 320º T, a difference of

80º, almost a right angle. All she had to do was point the plane along the shoreline and look at

her compass. If it said about 059º (allowing for 19º of west variation) she was north of Dakar and

if 339º she was south. No way to mistake this, there was no possible ambiguity. To make it even

simpler, the sun was setting in the west. If they had hit the coast north of Dakar then they should

have followed the coast to the southwest. If they had hit the coast south of Dakar then they

should have followed the coast to the northwest. Either way, if the sun was not in their eyes then

they were going the wrong way, didn’t even need a compass.

I think, for whatever reason (maybe better service available from the Air France facility,

personal contacts, etc.), they made a conscious decision to go to St. Louis and crossed the

coastline southeast of Dakar and proceeded overland to intercept the coast north of Dakar and

followed it to St. Louis. AE writes in "Last Flight"(page 119.)

"At St. Louis are the headquarters of Air France for the trans-Atlantic service, and I was grateful

for the field's excellent facilities, which were placed at my disposal."

Elgin Long thinks that they aimed directly for Dakar and that they passed west of Dakar and then

turned east and hit the coast north of there as Earhart said but there is a problem with his theory,

namely the 1800 Z LOP which showed that they had already passed the point where turning to

the heading Noonan had recommenced would have taken them to Dakar, and Noonan wanted her

to proceed even further to the northeast for another 36 minutes, 78 NM, prior to making the

turn. Most significantly, to the question of whether they accidentally missed Dakar, you can see

on Noonan’s chart that there had been a sun line that ran to Dakar on an approximate 21º T

course but this line was erased (but still visible) and the sun line was advanced to 1800 Z to run

to Saint Louis. This confirms that they deliberately hit the coast south east of Dakar and then

deliberately flew to Saint Louis. It's no coincidence that the 1800 Z sun line runs directly to Saint

Louis. and that the parallel line to Dakar had been erased. Long also fudged by stating that even

though they knew they were flying the wrong way, that Earhart knew that there were other

airports every 150 SM along the coast that she could go to. Even if this were true, they also knew

that the nearest airport to them was Dakar, it might be only ten miles to the southwest while St.

Louis could have been 100 NM ahead. He also wrongly claims that there were no airports south

of Dakar that they could have landed at if they had turned to the south and they were actually

going the wrong way. In 1934 an airport had been built at Bathurst and by 1937 it was in use for

scheduled trans-Atlantic airline flights to Rio de Janeiro. The 1836 Z position put them directly

over Bathurst or very nearby.

Ric Gillespie agrees with me that they struck the coast southeast of Dakar (but his chart work

was wrong) but he then comes up with an explanation that doesn't make sense for their failure to

simply follow the coastline northwest to Dakar. Gillespie claims that flying into the sun in hazy

conditions would have made it too difficult to follow the coastline. Gillespie is wrong because

the easiest thing to do in hazy conditions is to follow a coastline! Flying into the sun in hazy

conditions limits visibility and pilots don’t like to do it, not because it would be difficult to

follow the coastline but because of concern about bumping into another airplane. There were not

very many airplanes flying near Dakar in 1937!

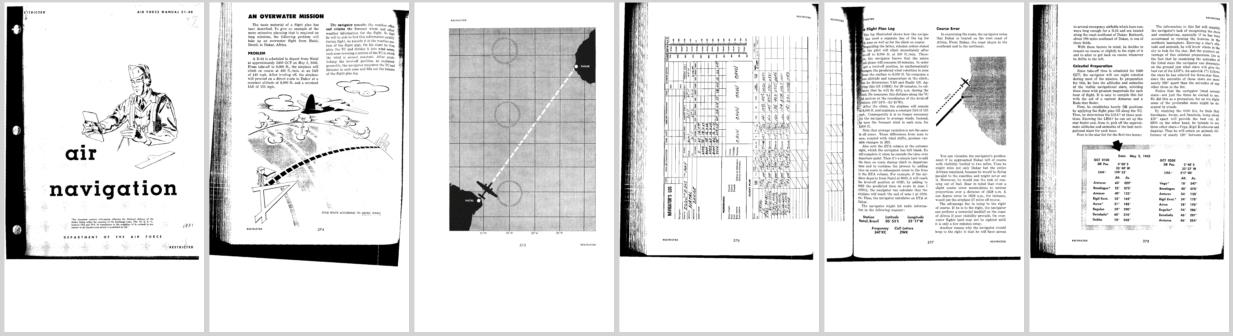

Earhart’s explanation was a complete fairytale, it never happened, and it is possible that note 2

was just a fabrication to support the fairytale since it makes no navigational sense. As further

proof that any competent navigator would have planned to hit the coast to the southeast of

Dakar, the Air Force navigation manual, AFM 51-40, uses this exact flight from Natal to Dakar

as the example of how to plan such a flight. (I have attached an excerpt from this manual, see

AFM-51-40.)

We may never know the real reason that they chose to go to St. Louis but it was an obvious

decision that they had made to fly overland to St. Louis instead of following the coast to Dakar.

The bottom line is that the Dakar flight provides no help in explaining

the final disappearance.

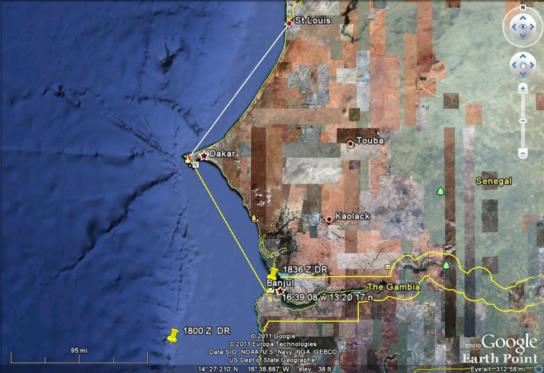

( I have also attached a Google Earth image that makes it easy to see the relationships.)

Gl

----------------------------------------------------------------

NavList message boards and member settings: www.fer3.com/NavList

Members may optionally receive posts by email.

To cancel email delivery, send a message to NoMail[at]fer3.com

----------------------------------------------------------------