NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2024 Mar 2, 06:52 -0800

Jim,

A few thoughts:

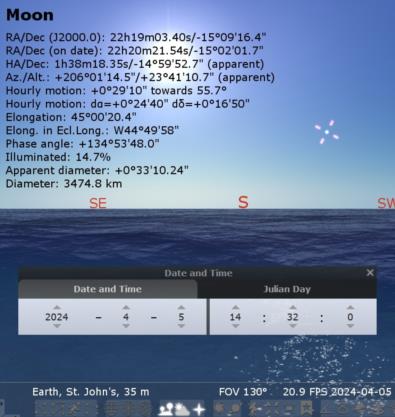

- Add the "Elongation" (and turn off half of the other parameters) to the visible data for objects in Stellarium. Elongation is astronomy jargon for an object's angular distance from the Sun. In the case of the Moon, "Elongation" is just another name for the center-to-center lunar distance. That will help you. See the image below.

- You're tossing around the phrase "in distance" (as in "the Moon is in distance") in an unhistorical fashion. As you learned in my lunars workshop, that phrase was used historically when the Moon-Sun distance was close to 90°. The latest example you've found on August 23, 1764 is for a Moon-Sun distance of 45° which would not have been termed "in distance" in the era when navigators were shooting lunars. That would not have been counted as a "great day for lunars".

- The Moon at a distance of 45° from the Sun is not easy to see. At that elongation, the Moon is a slim crescent only 15% illuminated [the fraction of the Moon illuminated is (1-cos LD)/2 where LD is the Moon-Sun angular lunar distance], and it's difficult, though not impossible, to shoot the Moon in daylight at that distance (elongation). You can test this yourself by finding dates when the lunar distance is close to 45° in the next few months (one example case in the image below). You can experiment in Stellarium, or you can check the tables on my website.

- Your examples here and your earlier post are not viable cases for longitude by lunar for a much more important reason. Local noon is one of the very worst times to get longitude using a lunar (or by almost any other method). It's a poor time to determine Local Apparent Time.

More generally, it's already established that Cook knew next to nothing about lunars as late as the beginning of the voyage of Endeavour in August 1768. ...So aren't you just fantasizing now? Without some kind of documentary evidence, this is not history. Furthermore, there is no mystery to the longitude on the Newfoundland chart. The observed eclipse is more than sufficient to pin down one longitude, and partly by luck (no doubt!) it was an excellent longitude. Local surveying work provided all the differences in longitude, the offsets that fixed the mapped "shape" of Newfoundland. The eclipse longitude placed that complex polygon in the proper east-west position on the global longitude network.

If Cook had employed actual lunars in Newfoundland, it would have been big news. Maskelyne would have trumpeted it from the top of St. Paul's. When experimental lunars were tried on a few East India vessels a couple of years earlier using Maskelyne's "British Mariner's Guide" to determine longitude from them en route, the results were sufficiently newsworthy that they were written up in the Philosophical Transactions (the Royal Society's "journal" and one of the most important scientific publications in the world at this time --and about as close as you can get to "trumpeting from St. Paul's" back then). Also, bear in mind that if Cook had observed any lunars during that Newfoundland project, unless there were careful matching observations from a known longitude, these would have yielded crude, low-quality longitudes, of no significance to the detailed chart that you're studying. Lunars constituted a developing technology in the 1760s. They would not yield high-quality longitudes for decades.

Frank Reed