NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2024 Feb 7, 15:50 -0800

Bill Ritchie, you wrote:

"My first glance caused my eyebrows to raise due to the absence of any atmospheric extinction near the horizon."

Exactly. That's what caught my attention. Otherwise, I probably would have scrolled past it. If the tool used to paint in the sky had included a simple facility to add increased extinction at low altitude, it would have been more convincing.

And:

"I assumed, therefore, that the image was a composite of at least two photographs, the sky one having been taken at a higher altitude than its transposed ‘apparent’ altitude."

Apparently, it's even simpler. This is now an "effect" in standard professional image-processing tools. You can paint in the night sky complete with Milky Way star clouds at will. Currently the tools are a little obvious, but inside a year or two I suspect that it will be relatively difficult to tell the difference. Then again, what astrophotography has ever been real, since the dawn of long-exposure astrophotography. The sky doesn't look like that. :)

"Though not a photographer, I would also expect that the necessary exposure to gain such stellar detail would be long enough for there to be some ship’s motion effects visible, especially so at the tips of the spars."

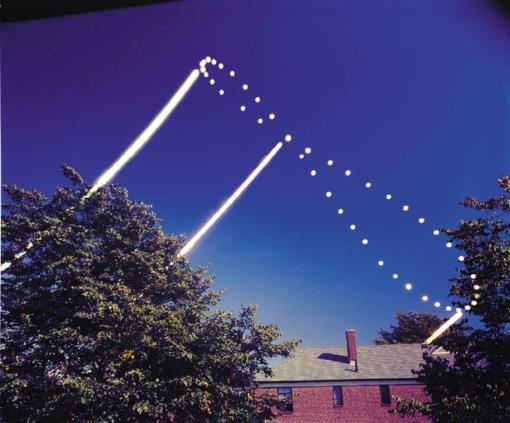

But, in fairness, even the most legitimate images in astrophotography (which is a slippery slope as I implied above) often use a double-exposure trick: photograph the sky with a long exposure or with a large number of shorter exposures amenable to stacking, then separately photograph the foreground with a short exposure and combine them later in processing. Or if you plan with great care, you can do this all on a single "piece of film". A good example of this process that comes to mind, especially this week as we approach "Sun Slow Day" is Dennis diCicco's year-long exposure of the analemma.

So what's that big glow up in the sky toward the right? Antoine Couette suggested it might be the Moon. Possible. Another possibility: the Sun. If we ignore all the stars and brighten the image a bit, couldn't this just be a daylight photo? I noticed when I zoom in on the vessel, there are quite a few people visible. Seems awfully busy for the middle of the night! So I suggest the base image here is just a sailboat motoring out for a tourist cruise on a nice sunny day. Then the Milky Way was painted in with one of those tools. If just a little more attention had been paid to the location of the horizon and the land in the distance on the left, this image might have been an excellent illusion. As it is, not so much!

Still an open question: where are you? What latitude and longitude would yield this sky? I am assuming here that we can continue to "pretend" that the sky is real. It still can yield some navigation interest. :)

Frank Reed