NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

Re: More on Charles Lindbergh's attitude to air navigation

From: Gary LaPook

Date: 2015 Jan 28, 08:51 -0800

From: David Pike <NoReply_DavidPike@navlist.net>

To: garylapook@pacbell.net

Sent: Wednesday, January 28, 2015 4:51 AM

Subject: [NavList] More on Charles Lindbergh's attitude to air navigation

I think it’s important to realise that whilst the Long Island to Paris flight was the one that suddenly made him famous, Lindbergh completed a large number of ‘trail blazing’ flights before and after his solo Atlantic flight. As navigation enthusiasts, we mustn’t forget that the main worry on the early long distance flights was the immediate requirement of simply keeping the engine going and keeping the aircraft in the air. After that, we can start to think about navigation. As Lindbergh says in his lecture, every flight is different. The navigational considerations flying from continent to continent are totally different to from trying to find a tiny island with no other land for hundreds of miles around. He seems to have been an early advocate of carrying a substantial surplus of fuel, and of the concept of a ‘point of no return’. He seems quite happy with the idea of turning back if the prospects of a safe landing ahead look poor. Moreover, Lindbergh was a professional pilot of some years flying experience, barn storming, military, and air mail, whereas it’s not uncommon for adventures such as Chichester and Earhart to take on massive explorations within a couple of years of learning to fly. (Noonan of course was a very experienced navigator). Lindbergh was also aware of the need to fly accurately. In the days of manual DR, one of the more significant sources of error was ‘pilot error’ i.e. the pilot not maintaining the course and speed required. Whilst not spending a lot of time on navigation during his Atlantic flight, Lindbergh was aware of the need to follow his flight plan accurately. Looking at Chichester’s Tasman Sea flight as described in ‘Alone over the Tasman Sea’, brave and resourceful as it was, the thing I find hardest to equate is the concentration upon sophisticated navigation techniques compared to the frightening way the aircraft and the instruments were behaving. The two things are not compatible, and if the latter was indeed true, one can’t help forming the opinion that he a very lucky pilot indeed.

So how does this get by without a wrap on the knuckles from Frank for being ‘off subject’? Well Lindbergh did indeed use astro in later ‘trail blazing’ fights which he fully acknowledges in the lecture below. (Figures in square brackets are ‘as spelled’; any other typing errors you spot are mine.)

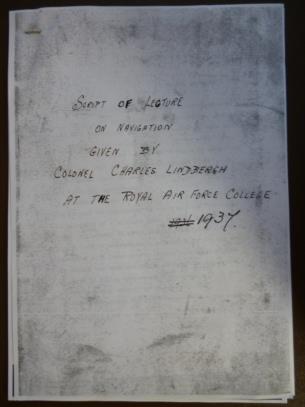

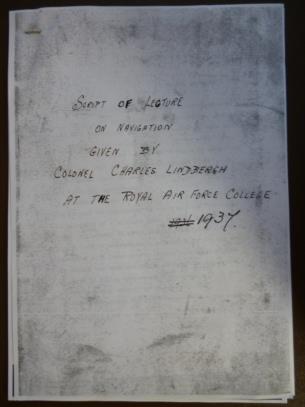

SCRIPT OF LECTURE ON NAVIGATION GIVEN BY COLONEL CHARLES LINDBERGH AT THE ROYAL AIR FORCE COLLEGE 1937

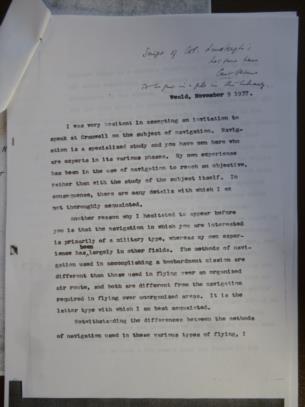

Weald, November 9 1937.

I was very hesitant in accepting an invitation to speak at Cranwell on the subject of navigation. Navigation is a specialized study and you have men here who are experts in its various phases. My own experience has been in the use of navigation to reach an objective, rather than with the study of the subject itself. In consequence, there are many details with which I am not thoroughly acquainted.

Another reason why I hesitated to appear before you is that the navigation in which you are interested is primarily of a military type, whereas my own experience has been largely in other fields. The methods of navigation used in accomplishing a bombardment mission are different than those used in flying over an organized air route, and both are different from the navigation required in flying over unorganized areas. It is the latter type with which I am best acquainted.

Notwithstanding the differences between the methods of navigation used in these various types of flying, I believe there is a certain underlying similarity which may cause experience in one method to contribute to competence in others. For instance, the experience of the air line pilot in maintaining his schedules under all weather conditions will undoubtedly be of value to the pilot of a bombing plane in time of war. Also, the problems encountered in navigating over unorganized areas have something in common with those found by the military pilot over enemy territory. One could hardly expect to obtain more assistance from the country he intends to bomb than from the tundras of the artic. Possibly the greatest differences between these two types of navigation would lie in the preparations made for a forced landing.

From the standpoint of navigation, aviation might be divided into three general classifications – commercial airline operation, military missions in time of war, and special flights of both military and civil aircraft.

The great difference between commercial flying and military flying seems to me to lie in the fact that in commercial flying we can plan on the greatest possible cooperation along the route, while in military flying we must plan on the greatest possible opposition. This situation makes the problems of the military pilot much more difficult and much more interesting.

If we look a few years into the future of the commercial airline, we will probably find passenger planes taking off, flying, and landing almost entirely under automatic control. This branch of aviation will no longer be subject to the whims of the weather, and its navigation may become largely a problem for the radio engineer. The sun, the moon, and the stars, will lose their old significance and the efficiency of science will once again replace the skill and character of man.

The navigation of military aircraft in time of war is not so easily standardized. Just what value radio will have over enemy territory is still a disputed question. The answer will not be obtained completely without actual experience, and probably not until the knowledge of radio itself has been developed still farther. A pilot must always lay plans for navigation which will be subject to the least possible interference. Consequently, the sextant and compass may prove to be the most important instruments of long range military aircraft.

It seems quite possible that cities will be bombed in the future, from high altitude and above clouds, by means of star sights. Existing bubble sextants make it possible to obtain a position within five miles. Probably three miles is a closer figure for an expert in smooth air, and the future development of the sextant will undoubtedly make the accuracy still greater. Of course, there would be no [markmanship] to such bombing, but tremendous damage could be done.

It may be argued that the effect of promiscuous bombing would not justify the cost, or that no enemy would carry out such an attack for fear of reprisals; but this is not a satisfactory [defense], and it is based upon the assumption that an enemy would always exercise equivalent judgement and logic.

Probably there is no factor which changes the relative value of the elements of navigation as greatly as war. A pilot is likely to find an enemy fighter instead of a radio bearing at his destination. The sun and moon again become of vital importance, and a storm is as likely to be a refuge as a danger. Even fog may prove a welcome friend at times. The military navigator must know how to use every element for the successful completion of his flight.

The third classification I have mentioned, that of special flights, covers such a variety of flying that it seems impossible to make any generalization about the navigation connected with it. These flights occur under every conceivable combination of circumstances. Sometimes it is possible to lay elaborate plans for their navigation, and sometimes their urgency and importance necessitates an immediate take off, with no preparation at all. A military mission[,] or a rescue flight may send a pilot out with inadequate equipment and no knowledge of the conditions he will encounter along his route. The success of such flights may depend upon the navigator’s resourcefulness in making the best of whatever instruments and information he has available at the time.

As pilots of the British Empire you are especially likely to be called upon to make flights in this category in the future. It seems certain that every passing year will see an increase in flying, both military and commercial, between England and he various portions of the empire. As military pilots you should be able to take your plane from any point on the earth’s surface to any other point. Sometimes you will be flying over organized airways, but often you will not. Your experience in navigation must fit you to judge the chances you will take in the light of the importance of your mission, and to take advantage of every instrument and circumstance available to make that mission a success.

Probably one of the most interesting ways of studying navigation is by taking definite flights as examples. I shall select three flights I have made, and outline briefly the conditions surrounding the flights, and the methods of navigation used.

I shall take a flight to India, which my wife and I made this spring, as representing one of the simpler problems of navigation.

We were in no hurry and did not object to being delayed occasionally by weather. Our plan of navigation was to fly when the weather was reasonably good, and to land or turn back if we encountered fog, or conditions of such low visibility that we could not maintain contact with the ground. Our navigating equipment consisted of maps, compass, altimeter, airspeed indicator, rate of climb indicator, directional gyro, and gyroscopic horizon. Our reserves lay in numerous areas where a landing could be made along our route, a large excess of petrol, and a pocket compass. Of course, we carried food, water, and equipment for about two weeks of ground travel, but that does not come under the heading of navigation.

As the second example I shall take a flight from America to Europe which I made in 1927. This flight necessitated the most careful preparation, although the navigation was not difficult. The danger lay in finding Europe covered with fog. Detailed and comprehensive weather reports were not available at that time, and radio was both heavy and comparatively unreliable. Consequently, I placed my reserve in an additional 1000 miles of fuel instead of extreme accuracy of navigation. If I encountered fog, I could probably have found an opening somewhere within a thousand miles of the coast, and I would have been satisfied with a safe landing anywhere in Europe. If the weather were reasonably good, there would be no problem in locating my position, even though I reached Europe far off course. My fuel reserve would have more than made up for any inaccuracy in navigation.

It is an interesting fact that a large navigating error in a long distance flight adds very little to the length of the flight if it is corrected for far enough from the destination. It is also interesting to note how the value of ground features changes with the length of a flight. In flying around an aerodrome, the smallest details give position, houses, groups of trees, fields, and fences. In flying from here to London, railroads and towns are good check points. But in long flights, the great geographical features take on their true importance, and mountain ranges, coasts, and watersheds overshadow the marks of civilization.

After a trans-Atlantic flight, the green hills and rock coasts of Ireland form an unmistakable landmark, far more reassuring than any radio bearing will ever be. Or if one flies south of Ireland and looks down on the cliffs of Cornwall, he could ask for no more definite location. And so along the coasts of Europe, from the Pyrenees to the Fjords of Norway, each country has its characteristics, clear and unmistakable. The problems in my navigation, then, depend largely on the weather I encountered, for even the most distinctive features disappear when they are covered by fog.

My equipment for this flight consisted of the necessary charts, an earth inductor compass, a magnetic compass, turn and bank indicator, pitch indicator, altimeter, air speed indicator, and drift indicator. I did not make use of the drift indicator due to difficulty of measuring drift while flying alone.

The third example I shall take is a flight from Lisbon to the Azores which my wife and I made in 1933. Of course, this was much shorter than either of the other two flights, but the problem of navigation was more intricate. The most difficult flights of all, from the standpoint of navigation, are those to an island with a great body of water on the far side. Unless you are able to carry a fuel reserve sufficient to return to the mainland, it is essential that the navigation be accurate. The alternative is a forced landing in open ocean.

A sextant and radio become of vital importance in this type of navigation. Without radio, one may arrive over the island to find it covered in fog. A sextant may be essential if the radio fails, or in directing a rescue party to your location in case of a forced landing.

Of course, it should be possible to reach the Azores by dead reckoning alone. My experience has been that a flight of this type can be made with an average error of less than 2o by using a compass, a drift indicator, and a directional gyro. However, the possibility of error is too great and the result of an error too disastrous to justify island flying without other safeguards.

For the flight to the Azores, our navigation equipment consisted of charts, two aperiodic compasses, a directional gyro, gyroscopic horizon, drift indicator, ground speed indicator, bubble sextant, two-way plane radio, directional loop, and an additional compass and waterproof two way radio set for use in a rubber boat in case our plane were damaged in a forced landing.

We were too uncertain of the radio facilities at the Azores to be willing to depend on the directional loop alone in reaching the islands. Also, we had experienced difficulty with our directional radio on several past occasions. It was a new type and not completely reliable. In consequence, our plan of navigation involved taking off from Lisbon at daybreak, and following a dead reckoning course, checked by observations on the sun later in the day.

The weather was partly cloudy, with local storm areas and varying winds up to gale velocities. We decided to fly to a point on our course where we would still have enough time to reach Lisbon before night if we returned. If at that time we had not obtained a check on our position by observations of the sun, and if we had not also obtained a radio report of clear weather at the Azores, we planned to turn back.

I shall not attempt to describe more flights as it would be possible to continue almost indefinitely without repeating exactly the same set of conditions. No matter how carefully emergencies are planned for, it is impossible to safeguard against every contingency. The incidents which are sometimes encountered in aviation can hardly be explained by the word coincidence. Perhaps they are best described in the words of the English scientist, who once told me that since everything that happened was infinitely improbable, he did not regard anything as surprising.

It often seems that mechanical failures occur at the most opportune time to cause trouble. For instance, the only time I have ever had the fluid leak out from a bubble sextant when I needed it was almost exactly half way across the South Atlantic. And the only time I have ever had two compasses go out of commission on the same flight was at night over the Straits of Florida. The sextant failure was not serious because the plane was equipped with radio and, as I have said, very accurate navigation is not essential in flying across the ocean, unless there is fog on the other side.

The failure of the two compasses, on the other hand, was more of a problem. Since it was in 1928, I had no directional radio. The failure [occured] about three o’clock in the morning. One compass was of the earth inductor type, and stopped functioning completely. The other was an ordinary magnetic instrument. It began rotating and never stopped. The night was hazy and only the brightest stars directly overhead were visible. They were so indistinct that I could not recognise any of them, and even they were soon covered by clouds.

The compass card turned very slowly during a part of its rotation and almost stopped at one point. I thought that this point might give an approximately correct position, and set my course accordingly.

I had a fuel range of about two thousand miles, and consequently, as long as the engine kept running, I knew that I would have no difficulty reaching land after daybreak. Sunrise would give me the general direction of east and if I were still over water, I could be sure of reaching the United States by setting a course to the north west. Whether I struck the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic coast was relatively unimportant. I hoped, however, that the course I followed from the rotating compass would find me over land at daybreak. I should probably add that that the reason I did not climb above the clouds and fly by the north star was that I had received a weather report, before leaving Cuba, to the effect that my entire route to St Louis was covered with low clouds, storms, and local fog.

Daybreak proved that I would have been wiser to have flown in a circle during the remaining hours of the night. I located my position over the [Bahama] Islands, about two hundred miles off course. I set course for Florida, relative to the lightest part of the horizon, and still had time to reach St. Louis before night.

The earth inductor compass did not function again until it was repaired. It is interesting to note, however, that the magnetic compass continued to rotate as long as I was over water, but stopped soon after I reached the coast of Florida. It oscillated excessively during the rest of the flight.

I have cited this instance as an example of how completely plans for navigation may be changed in an emergency, and how a pilot must sometimes rely on the most fundamental and natural factors in avoiding a serious accident, Fortunately, I had a fuel reserve which made up for the failure of my navigating equipment. If anyone should ask me what I consider the most important piece of equipment for air navigation, I would still be inclined to reply that it is an extra petrol tank. In my experience there has been no other item which has added as much to the safety and successful navigation of a flight as an excess of fuel.

In ending this paper, I wish that I could lay down a standard set of rules. When one first studies navigation [he] may obtain the impression that the same principles apply to all flights and that, like the alphabet, once learned its sequence is permanently fixed. Later, one learns that these elements are constantly changing in their relative importance; that they vary with the type of flying, with weather, altitude, air speed, fuel range, sunlight, ground organization, and many other factors. The methods of navigation used in various flights change almost as much as the arrangement of letters changes in forming different words. I can only emphasize the desirability of organising a flight around the simplest possible plans, considering first that everything will be right, and second, that everything will go wrong. So that one has reserves either for the failure of equipment or more complicated conditions. A pilot should attempt to build up his navigation so that every failure in his plans will leave him with another set which will still work. If the compass fails there is still the sun, and if fog covers the earth there is still the radio – and always that extra tank of petrol.

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Front-Resized.JPG: Open and save)

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Page-1-Resized.JPG: Open and save)

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Handwritte.JPG: Open and save)

From: Gary LaPook

Date: 2015 Jan 28, 08:51 -0800

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

I have had a particular interest in Lindbergh since one of my first flying jobs was hauling cargo every day from Chicago to Peoria Illinois in a single engine airplane, following the very same route that he had flown as an airmail pilot. I would look down on the same fields and rivers that he had seen. Luckily I did not

have to repeat his experience of parachuting out three time along that route when he had used up all of his fuel after being stuck on top of solid undercasts and unable to descend. I remember several times being in his exact predicament, clear blue skies above and solid white below from horizon to horizon but, I was in a holding pattern over the outer marker, airliners in the same pattern above and below me, awaiting my turn to fly the ILS instrument approach to the airport, an option that didn't exist in Lindbergh's time. It was always a happy time to see the runway lights when I broke out at 250 feet above the runway.

What Lindbergh said about the green of Ireland also brought back a clear memory. The first time I went to Europe I was ferrying a Cessna 172 solo from Newfoundland to the Azores and then on to Portugal and Brussels. It was celestial navigation for real with my A-10 sextant, and it was my first time crossing the ocean. I got several three star fixes and then a sunline showing me about 230 NM from Flores, the first island you come to, about 1050 NM from takeoff. There was a radio beacon on Flores and I was receiving it on my ADF, the needle pointing straight ahead, and I was on top of solid undercast. But then I was running late on my ETA for Flores, you start to get doubts, is there something wrong with my ADF? Then, for just a second, a small hole opened up below me and I saw the beautiful dark green fields with stone fences and then they were gone.

It was just for an instant. The pattern of those stone fences was etched in my mind. A couple of years ago I used Google Earth to look at Flores and I recognized the exact spot that I had seen more than 30 years ago. Yes, green fields are wonderful, they remove any self doubts about your navigation. I then continued another 350 NM to land at Santa Maria at the far end of the Azores.

The next leg to Porto Portugal was a snap, you can't miss Europe.

gl

From: David Pike <NoReply_DavidPike@navlist.net>

To: garylapook@pacbell.net

Sent: Wednesday, January 28, 2015 4:51 AM

Subject: [NavList] More on Charles Lindbergh's attitude to air navigation

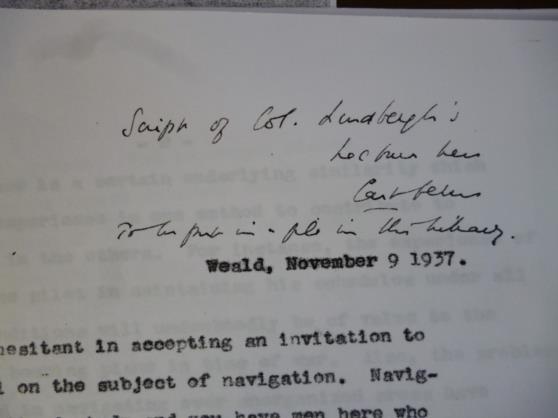

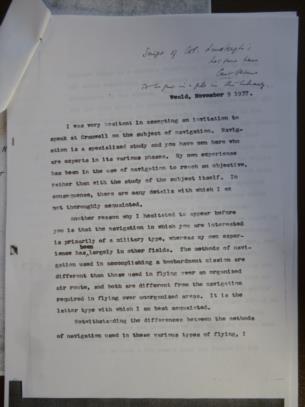

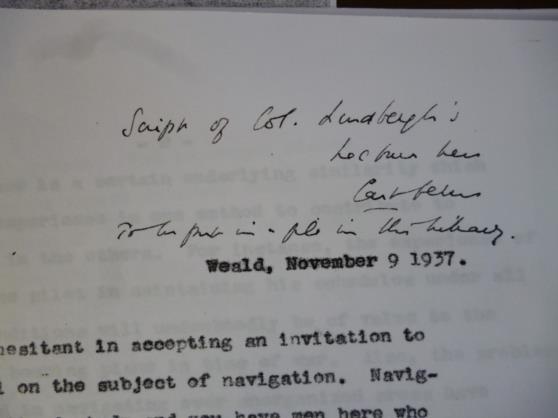

Some time ago I referred to a lecture given by Charles Lindbergh to cadet pilots at the RAF College Cranwell in 1937. I’ve now completed the courtesies and am now in a position to publish on this site the ‘soft copy’ I made a couple of years ago from the original held in the College Hall Library. I’ve attached a photo of the front and first page of the ‘hard copy’ original below (Can anyone decipher the two middle lines of the comment written by hand after the event?). The strong but fuzzy appearance of the typescript suggests it's a first carbon under-copy. It might be a typed up report of the lecture by a College shorthand typist, or it might be Lindbergh's actual script typed by himself or his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh. I favour the latter. There appear to be no 'listening' errors. It's written in double spacing for easy reading. It starts 'Weald, November 9 1937', and Lindbergh family rented 'Long Barn', Weald, Sevenoaks Kent from 1936 to 1938. There are several American spellings and Z appears for S on many occasions. Lindbergh subsequently became an accomplished writer. The paper is certainly smaller than foolscap (the UK standard at the time) and possibly wider but shorter than A4.

This was a very busy time for Lindbergh. It occurred around the time he was being entertained in Germany, viewing the Ju 88 and the Me109, meeting Goring, and forming his opinions upon the remainder of Europe's chances of resisting the strength of the Luftwaffe. Arguably, this coloured his writings from 1938 until Pearl Harbour when he sought unsuccessfully to be re-commissioned into the US AAC.

I think it’s important to realise that whilst the Long Island to Paris flight was the one that suddenly made him famous, Lindbergh completed a large number of ‘trail blazing’ flights before and after his solo Atlantic flight. As navigation enthusiasts, we mustn’t forget that the main worry on the early long distance flights was the immediate requirement of simply keeping the engine going and keeping the aircraft in the air. After that, we can start to think about navigation. As Lindbergh says in his lecture, every flight is different. The navigational considerations flying from continent to continent are totally different to from trying to find a tiny island with no other land for hundreds of miles around. He seems to have been an early advocate of carrying a substantial surplus of fuel, and of the concept of a ‘point of no return’. He seems quite happy with the idea of turning back if the prospects of a safe landing ahead look poor. Moreover, Lindbergh was a professional pilot of some years flying experience, barn storming, military, and air mail, whereas it’s not uncommon for adventures such as Chichester and Earhart to take on massive explorations within a couple of years of learning to fly. (Noonan of course was a very experienced navigator). Lindbergh was also aware of the need to fly accurately. In the days of manual DR, one of the more significant sources of error was ‘pilot error’ i.e. the pilot not maintaining the course and speed required. Whilst not spending a lot of time on navigation during his Atlantic flight, Lindbergh was aware of the need to follow his flight plan accurately. Looking at Chichester’s Tasman Sea flight as described in ‘Alone over the Tasman Sea’, brave and resourceful as it was, the thing I find hardest to equate is the concentration upon sophisticated navigation techniques compared to the frightening way the aircraft and the instruments were behaving. The two things are not compatible, and if the latter was indeed true, one can’t help forming the opinion that he a very lucky pilot indeed.

So how does this get by without a wrap on the knuckles from Frank for being ‘off subject’? Well Lindbergh did indeed use astro in later ‘trail blazing’ fights which he fully acknowledges in the lecture below. (Figures in square brackets are ‘as spelled’; any other typing errors you spot are mine.)

SCRIPT OF LECTURE ON NAVIGATION GIVEN BY COLONEL CHARLES LINDBERGH AT THE ROYAL AIR FORCE COLLEGE 1937

Weald, November 9 1937.

I was very hesitant in accepting an invitation to speak at Cranwell on the subject of navigation. Navigation is a specialized study and you have men here who are experts in its various phases. My own experience has been in the use of navigation to reach an objective, rather than with the study of the subject itself. In consequence, there are many details with which I am not thoroughly acquainted.

Another reason why I hesitated to appear before you is that the navigation in which you are interested is primarily of a military type, whereas my own experience has been largely in other fields. The methods of navigation used in accomplishing a bombardment mission are different than those used in flying over an organized air route, and both are different from the navigation required in flying over unorganized areas. It is the latter type with which I am best acquainted.

Notwithstanding the differences between the methods of navigation used in these various types of flying, I believe there is a certain underlying similarity which may cause experience in one method to contribute to competence in others. For instance, the experience of the air line pilot in maintaining his schedules under all weather conditions will undoubtedly be of value to the pilot of a bombing plane in time of war. Also, the problems encountered in navigating over unorganized areas have something in common with those found by the military pilot over enemy territory. One could hardly expect to obtain more assistance from the country he intends to bomb than from the tundras of the artic. Possibly the greatest differences between these two types of navigation would lie in the preparations made for a forced landing.

From the standpoint of navigation, aviation might be divided into three general classifications – commercial airline operation, military missions in time of war, and special flights of both military and civil aircraft.

The great difference between commercial flying and military flying seems to me to lie in the fact that in commercial flying we can plan on the greatest possible cooperation along the route, while in military flying we must plan on the greatest possible opposition. This situation makes the problems of the military pilot much more difficult and much more interesting.

If we look a few years into the future of the commercial airline, we will probably find passenger planes taking off, flying, and landing almost entirely under automatic control. This branch of aviation will no longer be subject to the whims of the weather, and its navigation may become largely a problem for the radio engineer. The sun, the moon, and the stars, will lose their old significance and the efficiency of science will once again replace the skill and character of man.

The navigation of military aircraft in time of war is not so easily standardized. Just what value radio will have over enemy territory is still a disputed question. The answer will not be obtained completely without actual experience, and probably not until the knowledge of radio itself has been developed still farther. A pilot must always lay plans for navigation which will be subject to the least possible interference. Consequently, the sextant and compass may prove to be the most important instruments of long range military aircraft.

It seems quite possible that cities will be bombed in the future, from high altitude and above clouds, by means of star sights. Existing bubble sextants make it possible to obtain a position within five miles. Probably three miles is a closer figure for an expert in smooth air, and the future development of the sextant will undoubtedly make the accuracy still greater. Of course, there would be no [markmanship] to such bombing, but tremendous damage could be done.

It may be argued that the effect of promiscuous bombing would not justify the cost, or that no enemy would carry out such an attack for fear of reprisals; but this is not a satisfactory [defense], and it is based upon the assumption that an enemy would always exercise equivalent judgement and logic.

Probably there is no factor which changes the relative value of the elements of navigation as greatly as war. A pilot is likely to find an enemy fighter instead of a radio bearing at his destination. The sun and moon again become of vital importance, and a storm is as likely to be a refuge as a danger. Even fog may prove a welcome friend at times. The military navigator must know how to use every element for the successful completion of his flight.

The third classification I have mentioned, that of special flights, covers such a variety of flying that it seems impossible to make any generalization about the navigation connected with it. These flights occur under every conceivable combination of circumstances. Sometimes it is possible to lay elaborate plans for their navigation, and sometimes their urgency and importance necessitates an immediate take off, with no preparation at all. A military mission[,] or a rescue flight may send a pilot out with inadequate equipment and no knowledge of the conditions he will encounter along his route. The success of such flights may depend upon the navigator’s resourcefulness in making the best of whatever instruments and information he has available at the time.

As pilots of the British Empire you are especially likely to be called upon to make flights in this category in the future. It seems certain that every passing year will see an increase in flying, both military and commercial, between England and he various portions of the empire. As military pilots you should be able to take your plane from any point on the earth’s surface to any other point. Sometimes you will be flying over organized airways, but often you will not. Your experience in navigation must fit you to judge the chances you will take in the light of the importance of your mission, and to take advantage of every instrument and circumstance available to make that mission a success.

Probably one of the most interesting ways of studying navigation is by taking definite flights as examples. I shall select three flights I have made, and outline briefly the conditions surrounding the flights, and the methods of navigation used.

I shall take a flight to India, which my wife and I made this spring, as representing one of the simpler problems of navigation.

We were in no hurry and did not object to being delayed occasionally by weather. Our plan of navigation was to fly when the weather was reasonably good, and to land or turn back if we encountered fog, or conditions of such low visibility that we could not maintain contact with the ground. Our navigating equipment consisted of maps, compass, altimeter, airspeed indicator, rate of climb indicator, directional gyro, and gyroscopic horizon. Our reserves lay in numerous areas where a landing could be made along our route, a large excess of petrol, and a pocket compass. Of course, we carried food, water, and equipment for about two weeks of ground travel, but that does not come under the heading of navigation.

As the second example I shall take a flight from America to Europe which I made in 1927. This flight necessitated the most careful preparation, although the navigation was not difficult. The danger lay in finding Europe covered with fog. Detailed and comprehensive weather reports were not available at that time, and radio was both heavy and comparatively unreliable. Consequently, I placed my reserve in an additional 1000 miles of fuel instead of extreme accuracy of navigation. If I encountered fog, I could probably have found an opening somewhere within a thousand miles of the coast, and I would have been satisfied with a safe landing anywhere in Europe. If the weather were reasonably good, there would be no problem in locating my position, even though I reached Europe far off course. My fuel reserve would have more than made up for any inaccuracy in navigation.

It is an interesting fact that a large navigating error in a long distance flight adds very little to the length of the flight if it is corrected for far enough from the destination. It is also interesting to note how the value of ground features changes with the length of a flight. In flying around an aerodrome, the smallest details give position, houses, groups of trees, fields, and fences. In flying from here to London, railroads and towns are good check points. But in long flights, the great geographical features take on their true importance, and mountain ranges, coasts, and watersheds overshadow the marks of civilization.

After a trans-Atlantic flight, the green hills and rock coasts of Ireland form an unmistakable landmark, far more reassuring than any radio bearing will ever be. Or if one flies south of Ireland and looks down on the cliffs of Cornwall, he could ask for no more definite location. And so along the coasts of Europe, from the Pyrenees to the Fjords of Norway, each country has its characteristics, clear and unmistakable. The problems in my navigation, then, depend largely on the weather I encountered, for even the most distinctive features disappear when they are covered by fog.

My equipment for this flight consisted of the necessary charts, an earth inductor compass, a magnetic compass, turn and bank indicator, pitch indicator, altimeter, air speed indicator, and drift indicator. I did not make use of the drift indicator due to difficulty of measuring drift while flying alone.

The third example I shall take is a flight from Lisbon to the Azores which my wife and I made in 1933. Of course, this was much shorter than either of the other two flights, but the problem of navigation was more intricate. The most difficult flights of all, from the standpoint of navigation, are those to an island with a great body of water on the far side. Unless you are able to carry a fuel reserve sufficient to return to the mainland, it is essential that the navigation be accurate. The alternative is a forced landing in open ocean.

A sextant and radio become of vital importance in this type of navigation. Without radio, one may arrive over the island to find it covered in fog. A sextant may be essential if the radio fails, or in directing a rescue party to your location in case of a forced landing.

Of course, it should be possible to reach the Azores by dead reckoning alone. My experience has been that a flight of this type can be made with an average error of less than 2o by using a compass, a drift indicator, and a directional gyro. However, the possibility of error is too great and the result of an error too disastrous to justify island flying without other safeguards.

For the flight to the Azores, our navigation equipment consisted of charts, two aperiodic compasses, a directional gyro, gyroscopic horizon, drift indicator, ground speed indicator, bubble sextant, two-way plane radio, directional loop, and an additional compass and waterproof two way radio set for use in a rubber boat in case our plane were damaged in a forced landing.

We were too uncertain of the radio facilities at the Azores to be willing to depend on the directional loop alone in reaching the islands. Also, we had experienced difficulty with our directional radio on several past occasions. It was a new type and not completely reliable. In consequence, our plan of navigation involved taking off from Lisbon at daybreak, and following a dead reckoning course, checked by observations on the sun later in the day.

The weather was partly cloudy, with local storm areas and varying winds up to gale velocities. We decided to fly to a point on our course where we would still have enough time to reach Lisbon before night if we returned. If at that time we had not obtained a check on our position by observations of the sun, and if we had not also obtained a radio report of clear weather at the Azores, we planned to turn back.

I shall not attempt to describe more flights as it would be possible to continue almost indefinitely without repeating exactly the same set of conditions. No matter how carefully emergencies are planned for, it is impossible to safeguard against every contingency. The incidents which are sometimes encountered in aviation can hardly be explained by the word coincidence. Perhaps they are best described in the words of the English scientist, who once told me that since everything that happened was infinitely improbable, he did not regard anything as surprising.

It often seems that mechanical failures occur at the most opportune time to cause trouble. For instance, the only time I have ever had the fluid leak out from a bubble sextant when I needed it was almost exactly half way across the South Atlantic. And the only time I have ever had two compasses go out of commission on the same flight was at night over the Straits of Florida. The sextant failure was not serious because the plane was equipped with radio and, as I have said, very accurate navigation is not essential in flying across the ocean, unless there is fog on the other side.

The failure of the two compasses, on the other hand, was more of a problem. Since it was in 1928, I had no directional radio. The failure [occured] about three o’clock in the morning. One compass was of the earth inductor type, and stopped functioning completely. The other was an ordinary magnetic instrument. It began rotating and never stopped. The night was hazy and only the brightest stars directly overhead were visible. They were so indistinct that I could not recognise any of them, and even they were soon covered by clouds.

The compass card turned very slowly during a part of its rotation and almost stopped at one point. I thought that this point might give an approximately correct position, and set my course accordingly.

I had a fuel range of about two thousand miles, and consequently, as long as the engine kept running, I knew that I would have no difficulty reaching land after daybreak. Sunrise would give me the general direction of east and if I were still over water, I could be sure of reaching the United States by setting a course to the north west. Whether I struck the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic coast was relatively unimportant. I hoped, however, that the course I followed from the rotating compass would find me over land at daybreak. I should probably add that that the reason I did not climb above the clouds and fly by the north star was that I had received a weather report, before leaving Cuba, to the effect that my entire route to St Louis was covered with low clouds, storms, and local fog.

Daybreak proved that I would have been wiser to have flown in a circle during the remaining hours of the night. I located my position over the [Bahama] Islands, about two hundred miles off course. I set course for Florida, relative to the lightest part of the horizon, and still had time to reach St. Louis before night.

The earth inductor compass did not function again until it was repaired. It is interesting to note, however, that the magnetic compass continued to rotate as long as I was over water, but stopped soon after I reached the coast of Florida. It oscillated excessively during the rest of the flight.

I have cited this instance as an example of how completely plans for navigation may be changed in an emergency, and how a pilot must sometimes rely on the most fundamental and natural factors in avoiding a serious accident, Fortunately, I had a fuel reserve which made up for the failure of my navigating equipment. If anyone should ask me what I consider the most important piece of equipment for air navigation, I would still be inclined to reply that it is an extra petrol tank. In my experience there has been no other item which has added as much to the safety and successful navigation of a flight as an excess of fuel.

In ending this paper, I wish that I could lay down a standard set of rules. When one first studies navigation [he] may obtain the impression that the same principles apply to all flights and that, like the alphabet, once learned its sequence is permanently fixed. Later, one learns that these elements are constantly changing in their relative importance; that they vary with the type of flying, with weather, altitude, air speed, fuel range, sunlight, ground organization, and many other factors. The methods of navigation used in various flights change almost as much as the arrangement of letters changes in forming different words. I can only emphasize the desirability of organising a flight around the simplest possible plans, considering first that everything will be right, and second, that everything will go wrong. So that one has reserves either for the failure of equipment or more complicated conditions. A pilot should attempt to build up his navigation so that every failure in his plans will leave him with another set which will still work. If the compass fails there is still the sun, and if fog covers the earth there is still the radio – and always that extra tank of petrol.

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Front-Resized.JPG: Open and save)

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Page-1-Resized.JPG: Open and save)

Attached File:

(f1-Lindbergh-Lecture-Handwritte.JPG: Open and save)