NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2024 Apr 26, 02:33 -0700

Murray Buckman, you wrote:

"Assuming a sun sight is to be taken, the whole horizon mirror would suit using the sun itself to find the index error, via the semi-diameter method."

Thanks. Yes, absolutely. That's the ultimate fallback method. It's been well-known since at least the days of Maskelyne. It's fairly straight-forward. And it's very accurate. But...

Novice navigators —and many experienced navigators, too— are uncomfortable looking straight at the Sun with the sextant set to zero angle. I have seen this many times. For a Sun-on-Sun index error test, we set the sextant to zero, swing in shades both for the horizon view and the index mirror view, and then point the instrument directly at the Sun. Although beginning students can be "talked into" this, many don't like it at all. They don't like it because they're not sure about the quality of the shades (and that's a real issue; I have recently seen poor shades on a brand new Davis sextant), and also because it's relatively easy to get little gaps around the shades and in other ways that leave the observer with a small bit of the Sun directly visible and blasting light straight into the observer's eye. This is at least unpleasant but it may be a risk for eye injury, too. For me that leaves this as the method of last resort, even for my own observations, but especially for beginners and occasional sextant users.

I have suggested in the past that we can use the contrails of aircraft at high altitudes for index error tests. They're miles away, as required for a proper index error test, and if the sextant is turned so that the contrail is "horizontal" in the field of view (perpendicular to the sextant frame), the contrail serves as a nice pseudo-horizon. This does work. It's easy and accurate, but I'm aware that I'm biased by my "home territory" experience. My local observing locations on land as well as in nearby New England coastal waters happen to lie under the great circle approach from Europe towards New York City (JFK airport in particular). Whether I'm at home in my backyard or teaching at Mystic Seaport or in Boston, I can regularly see crisp contrails, excellent for index error observations. Unfortunately my preferred observing locations are unusual in this case, and there are many areas at sea with very little high-altitude air traffic. So it seems that this is not a good solution either. :/

Whole horizon mirrors have become very popular. Maybe the relatively lower quality of index error checks by the standard sea horizon test is just a "cost of doing business" with this type of sextant.

A thought (just thinking out loud here since I can't sleep):

I observe the index error with my Davis sextant in evening twilight using a star-star test. That's accurate, easy, and there are no issues with dazzling sunlight or suspect shades. Then I immediately do a short-range index test from an identifiable, known location on my boat. For example, I stand exactly at some specific mark near the stern, and I shoot some bit of standing rigging near the bow. By the usual procedure this will give me a number "like" an index error, but it's not immediately useful because it's afflicted by instrument parallax. The distance is too short, and there's a "range finder" effect. Yet the difference between this short-range test and the proper index error should be a constant. For example, if my index error using the star-star test in twilight is 5' and the short-range test yields -20', then that difference of -25' should always apply even if the index error changes. So if I do my short-range experiment at exactly the same spot in my boat the following morning in daylight and get -10' then that would imply that the proper index error is 15' at that time. That should work... Maybe?

Another thought:

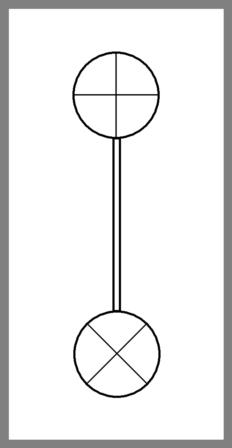

Maybe a short-range index error "target" eliminates instrument parallax... I make a little target consisting of two visual bullseyes separated by a few inches equal to the spacing between the direct and the horizon views of my sextant. This can be tested by first adjusting the instrument to zero index error (using a star-star test) and then picking the spacing to match. After I have made my target, I can hang it anywhere convenient on my boat, at any distance great enough to focus. I look at this target and adjust the view through the sextant so that the lower bullseye in the reflected (index mirror) view falls directly on the upper bullseye of the direct (horizon) view. The difference now is just the required "infinite distance" index error. I just tried this. Strictly in this one-off experimental setup, it works. Of course if it really does work, this could be done with any sextant and not just a sextant with a whole horizon mirror. After all these years, is a short-range index error test really that simple? Well, since I can't sleep... I can dream! ;)

There's a story I've read somewhere (is it in Lecky?) of a sextant merchant working in his shop and checking index error for customers by aiming at the roofline of a building across the street. In the story as usually told, we all get a good laugh at his ignorance. The target for an index error test should be at least a mile away, right? But maybe he had worked this out, and he was using a simple index error target, like I've described above —a shingle on the roof that was just the right size would work.

Frank Reed

Clockwork Mapping / ReedNavigation.com

Conanicut Island USA