NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2023 Aug 5, 07:34 -0700

Antoine, you wrote:

"First time I am ever playing with this kind of "Satellite navigation". I have been using heavens-above.com."

Glad you've had a chance to experiment with it! It's an amazing thing:

- no sextant needed,

- horizon required at all,

- potential accuracy of a tenth of a mile with good observations,

- easy accuracy of one mile with basic visual observations

Like you, I normally use heavens-above.com to analyze satellite passes like this, and also like you, I opt for trial-and-error. I have been trying to get folks interested in this method of navigation for roughly 15 years. Among celestial navigation enthusiasts, I find that interest is limited because "there are no tables". That is, there's no paper method that you can use to navigate this way. Also, there's no sextant required so all the usual skills of the celestial navigator get tossed out. Where's the fun in that? To which I answer: position-finding! That's the goal of navigation, and that's the fun here, too. Figuring out a position using back-and-forth trial-and-error in some app seems alien and appears to violate a basic principle of celestial navigation for many people. But the technique has so many useful features! I can guarantee this: at least one military service has created apps recently to use this method for position-finding in GPS-denied locations. Cameras in off-the-shelf smartphones have reached a point where they can be applied directly and easily to this navigation process.

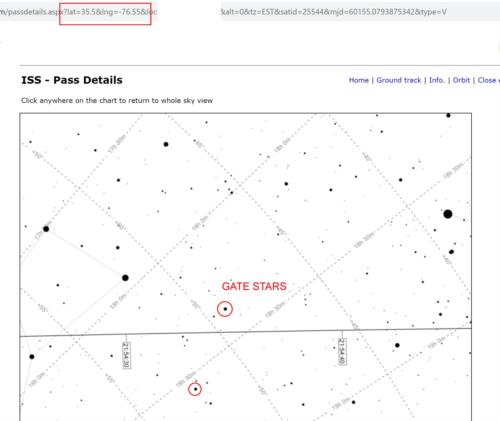

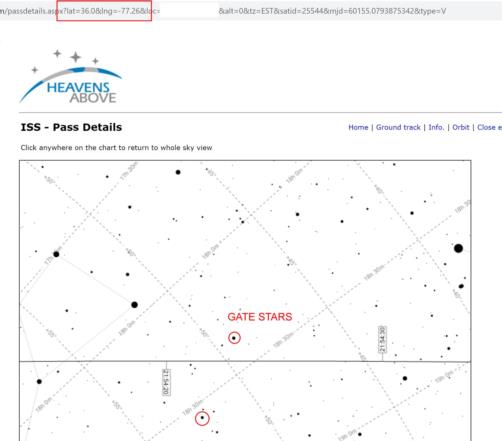

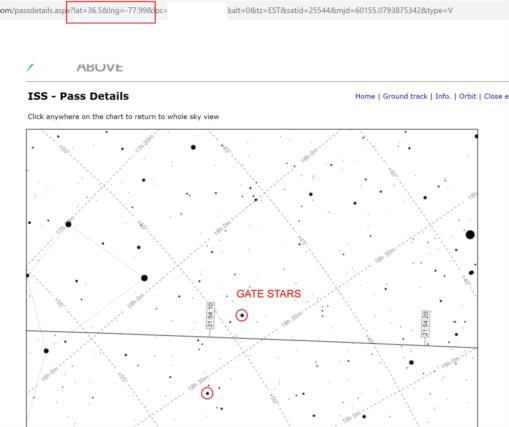

When I'm observing satellite passes visually for position-finding, I look for a stair pair as a "gate" that the satellite passes through. This gate should consist of two reasonably bright stars, brighter than let's say, magnitude 4.0 and separated by less than 5°. The pair should be arranged so that the line through the stars crosses the satellite track across the sky at a wide angle, 45-90°. Ideally, I watch the satellite pass through that "gate" and I record two things: the fractional distance across the gate, for example "40% of the distance from the northerly star in the pair to the southerly" and the time to the nearest second or even tenth of a second if possible (satellites move fast and one second in Low Earth Orbit typically translates to four miles on the ground). We can do the same thing with satellite photos, like the one that started this story, but of course we probably do not have access to the exact time.

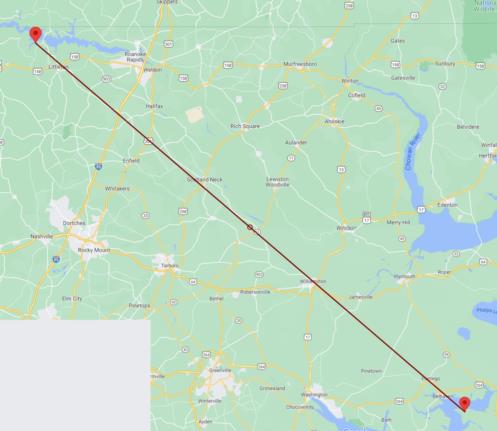

I picked a gate pair in the original photo (see images, attached below), then found those in the heavens-above star charts, and then picked some latitudes in the vicinity of northern North Carolina which was my "DR position" for this scenario. Then it was just a question of adjusting the longitude until the satellite track passed through the gate at the correct fractional distance across the gate. Note that this is really very similar to the methodology that you used, Antoine. I also double-checked the generated satellite positions in Stellarium which also produces excellent results for satellites though it can be difficult to get the satellite you want to show up in the display (I haven't detected any pattern to this anomalous behavior). Though I didn't use it for this scenario, I should also mention in-the-sky.org which has some excellent tools: https://in-the-sky.org/spacecraft.php?id=25544.

Ignorance of the exact time is not a critical loss, and it also covers the most important uncertainty in a satellite's orbit --an incorrect mean longitude in the orbit. If a satellite's orbital elements are a few days or a week old (even older can still be useful in many cases), the satellite will experience various orbit perturbations, especially uncertain air drag, which will delay or advance the satellite along its orbit by some few or some dozens of miles. This is an error "on-track" displacing the satellite forward or backward along its apparent track on the sky. There is much less error "cross-track" pushing the satellite left or right. This on-track error is essentially identical to a timing error. If a satellite is "early" on its orbit by, let's say, ten seconds, this is almost identical to a watch reading error of ten seconds. So if we assume uncertainty in timing in the analysis, we automatically cover the most important uncertainty in a satellite's orbit, too.

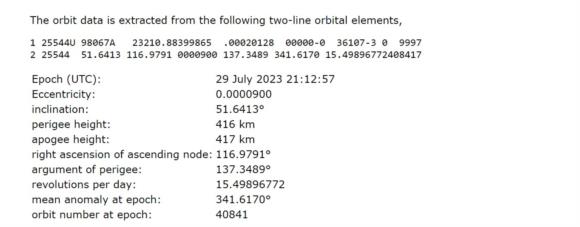

Images of my analysis attached. I hope they're mostly self-explanatory. I have included the orbital elements for the ISS at the time of my original analysis. These change regularly (since the space station is carefully monitored, of course). It's interesting to consider how long a stale orbit can be used for position-finding like this. One issue to consider here: the orbit of the ISS is "maintained" --boosted to counteract drag-- so if we want to consider an old set of orbital elements, it might be useful to reduce or zero out the orbital drag term.

Antoine, I may have mis-read (and I'm really short on time this week), but I think you mentioned a Mercator projection for your plotting. Does it matter? If you plot both the satellite line of position and the Vega line of position by lat/lon pairs, then you don't have to worry about projection, right?

Frank Reed

PS: I don't think I said earlier: nice work identifying Vega! And nice analysis for the hypothetical altitude sight.