NavList:

A Community Devoted to the Preservation and Practice of Celestial Navigation and Other Methods of Traditional Wayfinding

From: Frank Reed

Date: 2018 Feb 25, 14:05 -0800

Bob, you wrote:

"By 'capable', I mean they are good enough that they can plot an LOP at will, without having to go back to a textbook all over again to work out the steps of doing a sight reduction."

I would argue that this standard is probably too high. This is more like asking who could pass an exam. In all areas of life, we have practical tasks that we "know" how to do, but we consider it normal to review the topic in detail before we do it in practice. And in navigation, that's what I recommend. How many people would have the opportunity to use celestial with a frequency greater than a few times a year? But it's quite possible that a navigator has done real celestial navigation within the past year but right now can't recall the steps to use tables or the equation to punch up on a calculator. That's not an incapable navigator --just a little stale!

I was talking with a friend last week about various software development tasks. We discussed the issue of setting up the styling and aesthetic appearance of a website. This is done using a rather intricate --but fundamentally simple-- language called "CSS". It's one of the three elements of a modern website: one language, called HTML, is used for semantic structure, another language, CSS, is used for styling and user interface details, and a third languge, javascript, is used for interactivity, site behavior, and almost everything that is dynamic (I'm excluding server-side features, which are a whole 'nother ball 'o wax). I can honestly say that I "know" how to use this CSS language. But I keep a handbook nearby whenever I need to use it because there's no way that I can remember it all unless I specialize in it to the exclusion of all else. Notes are normal.

Now celestial navigation is ten times less involved than styling a website, so I could persuade people to memorize it all, if I felt it was desirable, but I just don't see it. You need to learn the concepts and you need to use some subset of the tools, and you need to learn what components of it you can easily re-learn rapidly, on-the-fly. My philosophy of navigation education is, in fact, founded on this idea that modern celestial navigation should assume that navigators will normally review the subject before they will have the pleasure of using it, and they will have access to notes. And that means that many of the pointlessly intricate components get thrown out. They make rapid re-learning less feasible. At the same time, I assume that this review should be possible in the space of a few hours at most, ideally less than half an hour. That's feasible.

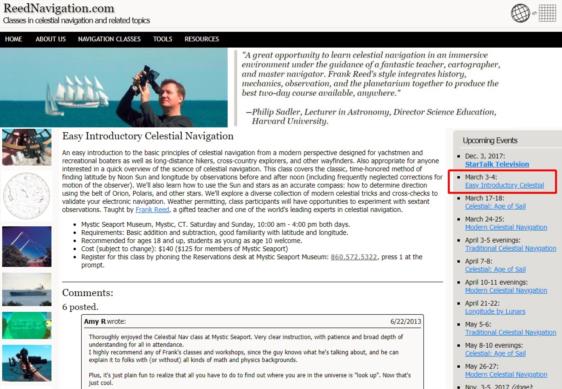

There are also varying degrees in the type of celestial navigation. The largest fraction of celestial navigators have crammed for the exam and that's all they really know. For six weeks they're quite competent, but they'll lose it all within perhaps three months. Since there are so many of them, their numbers fresh out of school might be the biggest group to pass your standard to qualify as navigators. Other navigators, less exam-focused but still driven by the syallabus behind the exams may learn the intercept method, and study the details of the official Nautical Almanac, and learn the ins and outs of a specific method of sight reduction tables, like HO 229, and might learn how to manipulate the old star finder. This would make a person a standard late-20th century celestial navigator, but not necessarily a competent celestial navigator. Yet another celestial navigator might learn to clear sights using software on a calculator or some other basic device and only do noon latitudes by manual navigation. Still another navigator might learn to get latitude at noon by simple calculation and longitude by sights around noon, looking for the axis of symmetry and all that. In fact, that's what I'm teaching in my "Easy Introductory" class this weekend (see below). This last is a type of navigation that is less flexible than the full-blown set of tools, but you can sail the globe with it, and it is very easy to review and re-learn.

I'll suggest a different measure by which to count the world's celestial navigators: how many people shot a celestial sight with a manual instrument like a common sextant within the past year and used it in some fashion immediately after taking the sight to get useful navigational information, outside of a school or classroom scenario, whether they had to review using a book or not? I would estimate 5000 at sea, maximum. If we include folks practicing and experimenting on land, I would estimate the total rises to 25000. These are just my best guesses. Notice that the number of people who might say "I didn't take sights ... but I could if I really wanted to" would probably be ten or twenty or even fifty times higher. But I feel that practice beats intentions. And while navigation can be a hobby, that is not its fundamental nature. If you don't do it ...and don't do it for navigation, it doesn't count. :)

Frank Reed